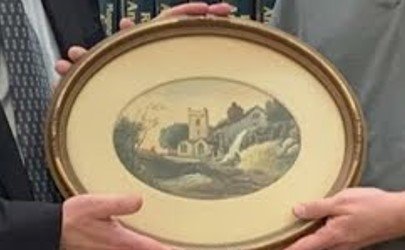

When Michiko Quinones first saw the framed, oval-shaped 1864 watercolor of a tiny Black man peacefully fishing near a mill, she cried.

It wasn’t the serenity of the running water or easy sway of the branches that put Quinones in her feelings. Nor, was it the image of a Black man enjoying a moment of peace at a time when African Americans — both free and enslaved — were terrorized without recourse.